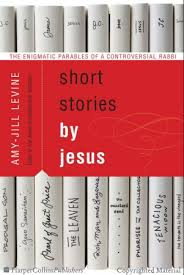

If you've been in a bookstore or on the internet or near oxygen you're probably familiar with the name Amy-Jill Levine. I am very excited about her new book and fortunate to have interviewed her about it. The book is called Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of a Controversial Rabbi and it will change the way you read some of Jesus' most celebrated teachings. My guess is that this book will invite as much controversy as it does reflection; few readers will walk away from the book unchallenged. Such is to be expected from a teacher as talented as Amy-Jill Levine.

ACL: Professor Levine, thank you for providing us with such a fascinating read. Your research casts many of Jesus' most familiar stories in a new light. Did you ever find yourself surprised by one of the parables as your book was unfolding? In other words, did you ever have the experience of thinking that your research would take you in one direction and then find an altogether different line of thought emerge?

ACL: Professor Levine, thank you for providing us with such a fascinating read. Your research casts many of Jesus' most familiar stories in a new light. Did you ever find yourself surprised by one of the parables as your book was unfolding? In other words, did you ever have the experience of thinking that your research would take you in one direction and then find an altogether different line of thought emerge?

AJL: Thank you for your kind words.

The major surprise I had was that what seemed so clear to me

was not often noted in commentaries and even less noted in sermons. Given the

increasing interest, in both theological and academic circles, in Jesus as a

teacher of justice and ethics, I had expected to find comparably less focus on

how Jesus saves our souls for the afterlife more focus on how Jesus saves us

from damaging relationships with other people.

What also surprised me -- not because if its presence (which

I expected) but because its extensiveness -- was the frequent

mischaracterization, through ugly and ahistorical stereotypes, of Jesus’ Jewish

context. In interpretation after interpretation, Jewish theology and practice are

used as Jesus’ negative foils and thus the interpretations bear false witness

against both Judaism and Jesus.

ACL: You make a compelling case that Jesus' stories were not

exactly meant to be enjoyed by his hearers. In many cases, Jesus seems to

intend his parables to cause discomfort. You remind your readers that religion

often functions "to comfort the afflicted and to afflict the

comfortable." You explain, "We do well to think of the parables of

Jesus as doing the afflicting." To what extent is this an apt description

of Jesus himself? Was Jesus someone who aimed to afflict those who occupied

"comfortable" stations in his society?

AJL: All people, regardless of class or station, have

comfort levels. We often today think of Jesus as condemning the rich and strong

and uplifting the poor and weak. That's too simple, and the formulation of

rich/strong vs. poor/weak creates more problems than it resolves: it

essentializes the categories into “us” vs. “them”; it tells the poor that they lack

power; it causes the rich to look at the poor as victims, and it causes the

poor to look at the rich as enemies. The Parable of the Prodigal is, on my

reading, about families and not about social station. The Parables of the

Workers in the Vineyard challenges anyone who has employment when others do

not. The Parable of the Widow and the Judge calls all comfort levels into

question, and so on.

ACL: You say that the story of the prodigal is about family

and I think you make good sense of this parable in your book. But this is where

the parable is particularly challenging for me. Elsewhere Jesus seems to have

an altogether bizarre understanding of family. In many places, Jesus seems to

undermine family honor. Do you see the story of the prodigal to fit well within

Jesus' other sayings? Or is this parable something of an outlier?

AJL: The prodigal is about counting, wherever: family,

community, synagogue. It is about making sure no one is overlooked, and

especially about making sure that those who may feel discounted are not. Every

person is precious. In terms of Jesus and the family and honor, three comments.

First, Jesus sets up an alternative family (of mother and brother and sister —

there could be more than one mother in the household, as Jewish practice in the

land of Israel at the time was polygynous). Second, he does talk about

disruption in the family (or at least this disruption is attributed to him via

a citation of Micah 7.6 in Matt 10.35), but he also insists on honoring father

and mother (e.g. Matt 15.4). Thus the message about the family is complicated.

Third, I think the honor/shame model is overplayed in much NT study. While it

can be informative, it — like much of the macro sociological modeling — typically works out so that the social conventions are, from a twenty-first

century perspective, negative, and Jesus becomes the counter-cultural hero who

stands against them. Thus instead of having an unbiased, culturally aware

reading of ancient society, we get elegant apologetic.

ACL: The concept of the "kingdom of God" (or just

"kingdom") features in many of Jesus' parables. Your book reexamines

a few such parables. In very simple terms, would you explain what (the Synoptic

presentation of) Jesus has in mind when he uses this concept?

AJL: I cannot “explain” the kingdom. For the kingdom, or

love, or even theology, we do not have adequate words. Hence the best way of speaking

about the kingdom – both present and future; both among us and within in; both

extraordinary and mundane – is through parable or poetry, metaphor or simile, art

or music. How do we understand the kingdom: we understand it, in part, as we

understand love. We know it when we see it; we feel it arise inside of us, or

we feel it possess us from above; we can study it and attempt to dissect it,

but it will always remain mysterious.

What I can do is explain– in an act of informed imagination

– is how the parables might have sounded to Jesus’ Jewish audiences. They would

have heard teachings that told them what they already knew but had ignored, or

suppressed, or taken for granted. They would have been challenged to see the

world otherwise, as it could be and should be. More, they would have been

challenged to help create this new world. If the parables leave people feeling

complacent (e.g., being happy that they’re ‘saved’ or being relieved that

they’re not like Pharisees), then the kingdom is not present in their reading.

ACL: In your treatment of the parable of the vineyard

workers, you argue that the parable is first and foremost about economics. If

so--in your estimation--what has caused so many Christian readers and preachers

to turn it into an instruction about salvation?

AJL: There are numerous reasons why readers have emphasized

soteriology over economics. These include (1) resistance to anything that

smacks of works righteousness, (2) a sense that religion is about the soul and

not about society, (3) (unthinking) anti-Jewish views wherein Pharisees (or

Jews) are disinterested in sinners repenting or gentiles worshiping the G-d of

Israel (the role here of Judaism as the negative foil), (4) a view of Jesus

derived from the creeds wherein the incarnation and the cross take preeminence

over the teaching, and (5) the view from (some) pews that ‘we’ are the poor

(the good guys, who repent and are cleansed of our sin) rather than the problem

(the folks who are not loving our neighbors as ourselves).

ACL: What's next on your to-do list? Do you have another

book in mind or in the works?

AJL: I’m trying to finish (1) a commentary on the Gospel of

Luke (which I am co-writing with Ben Witherington III), (2) an edited feminist

commentary on the Gospels for an international consortium (the Spanish, German,

and Italian translations are already published), (3) the last (14th) volume of

the Feminist Companions to the New Testament and Early Christian Writings (on

the Historical Jesus), and (4) a volume on Mary and Martha (co-authored with

Scott Spencer). The next major project will be probably be a volume on the

ethics of Jesus. For that, I need a Sabbatical. The vast majority of my time is

taken up in teaching, grading, class preparation, and student consultations.

My sincere thanks to Professor Levine. I would highly recommend this book for a variety of adult education settings. It is wonderfully accessible, but never banal. I guarantee that it will generate discussion and encourage critical thought.

-anthony

Terrific interview, Anthony. Thanks, A.-J.!

ReplyDelete